I recently wrote an article for an adoption blog on attachment issues. While this article was meant for those who have children with complex trauma backgrounds, the theory of attachment is applicable to all.

Our underlying view of attachments will shape the way we experience others and relate to them. I hope you find this article useful on your journey towards greater self-awareness.

When Attachment Hurts

The buzzword in the adoptive community is, unequivocally, attachment. For those who have never adopted or fostered, this word may have vague associations with dusty textbooks and archaic research studies. But for those of you who have chosen the joyous and painful journey, this word has flesh and bones to it, in the form of your child.

The historical, prevailing wisdom dissected attachment into four categories. These categories had a variety of names, all with similar, delineative meanings: Secure/Balanced; Anxious/Enmeshed; Avoidant/Detached; and Anxious-Avoidant/Ambivalent.

From my perspective, this view of attachment anaesthetizes the true complexity of it, and by doing so, diminishes how adoptive parents experience it in real time. It also leaves these parents with an incomplete framework for understanding the rapid-fire emotional changes they witness in their traumatized child, and it gives little insight into managing those changes. An example?

Cheerio Confusion:

One moment your child is clinging to you at breakfast, with loving arms encircling your neck. The next moment she screams and smashes the cereal bowl following a simple request to wipe Cheerios off the table. That same child, who was just doting on you, is now reminding you that you’re the worst parent ever, there’s never been anyone more horrible than you, and she wants to hurt you. You’re bewildered. You ask yourself why this is happening when the same request the day before yielded swift compliance—a completely different response.

Does reading this bring validation, intense emotions, or your own physical reaction? If you said yes to any of these, then chances are you’ve experienced this, first-hand. This attachment pattern is the most confusing and troublesome for adoptive and foster families.

Now bear with me while I get theoretical. It’s important to have a framework that demystifies this experience.

While a traditional attachment view would say that the girl in our story has an ambivalent attachment, confining her to that box misses the fact that this style is a combination of two other attachment patterns.

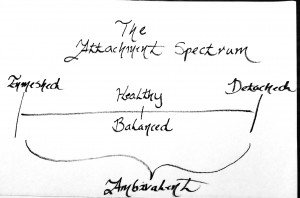

Rather than compartmentalizing attachment styles as secure, insecure, enmeshed, and ambivalent, I prefer to view attachment along a spectrum. Take a look at the picture. Think of it as a fulcrum, where the closer you are to a secure attachment, the more balanced the scale. When you move along the fulcrum to one side or the other, it tips. So the middle represents an emotionally balanced connection.

On one side of the spectrum is enmeshed (clingy), the opposite of this is detached (avoidant or hostile), both are equally insecure attachments. The fourth style, ambivalent, is demonstrated at the bottom of the diagram as a patterened response of moving between one end of the fulcrum and the other—between detachment and enmeshment. The more extreme the attachment disorder, the more likely we are to live between the two ends of the scale, rapidly pinging back and forth. For those exhibiting an ambivalent attachment, the imbalance is dramatic and polarizing. The point, here, is that this type of imbalance quickly creates chaos.

Unlike a compartmentalized view of attachment, this spectrum view presumes that all of us have dynamic attachment patterns. We all move along the spectrum and the frequency and severity of that movement depends on the amount of stress we’re under. This means that I’m not defined by being anxious, or avoidant, or insecure in my relationships, I will move between those descriptors, along the fulcrum, depending on my level of stress.

So why does this matter to you?

The more ambivalent your child’s attachment pattern, the more easily they kick up your own stress. How many of you feel like, during crisis moments, your internal, emotional state reflects that of your child? How many of you feel guilty when the same angry insults they are hurling at you are rising up in your mind regarding them? Don’t. You’re being triggered. Rather than judging yourself, know that you’re under tremendous stress, and the chaotic emotions you feel mirror what they’re feeling too.

The good news? They can move from the edges of the spectrum closer to the middle. The other good news? So can you.

Rather than trying to move your child from one attachment “category” to another, you can think in terms of lessening the frequency and duration of their polar responses between enmeshed and detached.

If we’re aware of how these traumatized children are moving across the spectrum of attachment, we can better understand how to tailor our responses. De-mystifying this experience is the conquered first step.

Once you understand this, the next step is to consider how to calm yourself down when their shocking responses are programmed to suck you in to their emotional vortex. If you’re drawn in to the chaos, the likelihood of the two of you overreacting is high.

Now, let me make this very clear: This. Is. Not. Easy.

I have tremendous respect for those who have made the decision to foster or adopt. And working with a child who exhibits this ambivalence on a regular basis is very difficult. So any suggestions I make or insight I offer I do with the understanding that this is painful and exhausting.

It’s for this very reason that it is essential to find a supportive community that understands adoption, to provide support and resources during crisis.

There are two traps I see parents fall into. And the first trap initiates the second. First, they view the attachment as overly fragile. Because many parents have been indoctrinated with the importance of healthy attachment for their child’s healing, they often believe they have to tiptoe around the child with the utmost sensitivity, which ends up being burdensome, exhausting, and can lead to increased triggered responses on the parent’s part, as well as tension and anxiety for the child, who is attuned to your responses.

The second trap is that because of this fragile view of attachment, parents are so concerned with maintaining the connection in order to generate healing that they end up living in enmeshment while believing they’re creating a healthy attachment.

What does this look like in real time?

Long, drawn out conversations about emotions and copious amounts of time spent trying to engage your child to facilitate the connection (the belief being that time spent correlates with attachment security). In reality, spending too much time in emotional conversations with your child increases the likelihood that you both become stressed and you both overreact.

Parents’ hypersensitivity to their child’s emotional cues will likely increase their child’s hyper-vigilance. And if the parents view the attachment as fragile, this will increase their sensitivity to the child’s cues. It’s a vicious cycle.

The number one way to combat this is through awareness. You need a clear understanding of the landscape to know how to respond. Picture the attachment spectrum in your head; consider where you fall on that spectrum during moments when you’re most upset. Do you tend towards anxiety? Avoidance? Or toggle between both?

Now, what do you notice about your child? Can you pinpoint where they are on that spectrum during times when they’re upset? What would it look like to view them as more resilient? What would it look like to stay calm while they are in crisis? What do you need to remember from what you’ve learned, here, to be able to do that?

For traumatized children, we can respect the nature of their attachment to us without being overwhelmed by its fragility. Putting language to the interaction patterns with them will allow us to better understand their actions and our reactions, moment by moment. As we begin to understand those and get perspective on the obstacles we’ll face, we open the doorway to incorporating interventions and experiencing them, and ourselves, with greater resiliency.

Buried beneath their stressed responses are the personalities of some really awesome kids, full of vibrancy, curiosity, and creativity. And buried beneath your stressed responses, you’ll find the reflection of your former self, the pre-adoption part of you that was also more vibrant and more curious. I bet you’re longing to see that.